Note Taking System For Success in Academia

Say Goodbye to Microsoft Word and writer's block. Welcome Obsidian and the SCTO methodology to gather and store your knowledge. Build understanding and make it fast and easy what and how to write.

My Blog has moved

If you want to receive updates, new content, and tips, head out to my website.

As academics knowledge is everything for us. Structure is that which enables us to create new knowledge from existing knowledge. It enables to see new connections, identify gaps, and direct our efforts.

This article is about structure. The SCTO System presented here, will hone your critical thinking, speed up your writing and find knowledge in no time.

Having a system of taking notes is like having a librarian for your brain, where knowledge can be very quickly retrieved and traced back to primary sources.

Or think of it like having a shoe for your brain that allows you to run (i.e. think) faster with more comfort, confidence, and ease.

Like every shoe, it will take a bit of getting used to it - but after a few hours you will see the first benefits and after a few days you will start making adjustments suited to your needs. You will develop the system to precisely fit your domain and style.

To indulge in this new affair with information, you have to promise me one thing:

Break up with Microsoft Word…

Most academics use Microsoft Word. Mostly out of habit, familiarity, and lack of time to look out for something better. But Word has a fatal flaw when it comes to note-taking: **It is not interconnected**.

Why do you need to connect notes? Simple, because this is how your brain works: "I wonder if the method I read in Paper A could be applied to the problem in Paper B". We think by association, so we need to take notes to follow this natural flow of our thoughts.

Our brain is not a database, it is a network. The more we align our notes with the network framework, the more powerful they become as an extension of our thinking.

…and Fall in Love with Obsidian

This interconnectedness is where Obsidian excels. Go ahead and download the software - we will see how to use it in an instant.

A bonus is that Obsidian is open source, free and your notes remain on your computer. As opposed to Notion, Evernote, Google Keep, Apple Notes, etc. Your notes are yours, and if you ever decide to move (even back to Word), you own them.

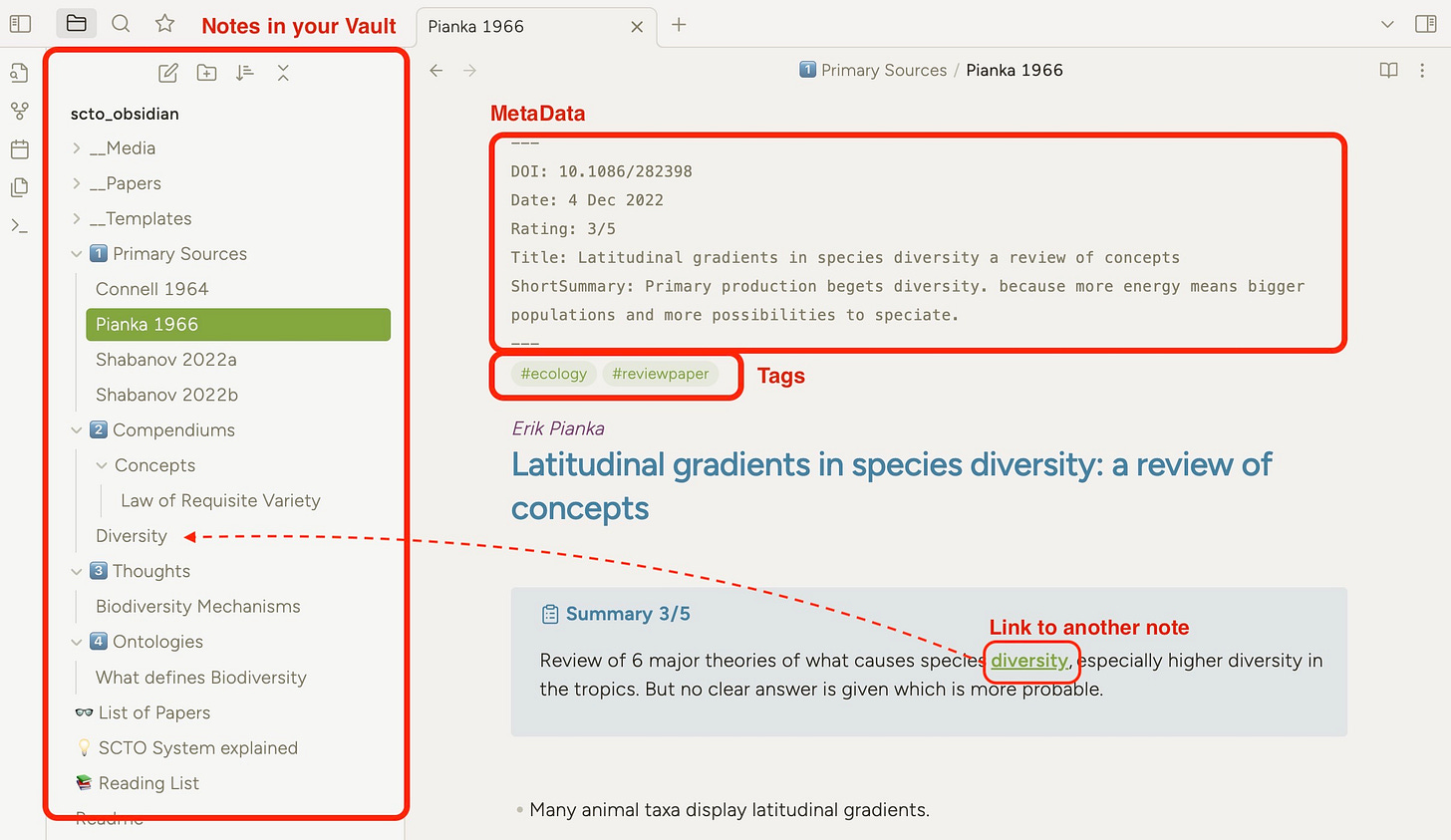

A 3-Minute Intro to Obsidian

At its core Obsidian is not very complicated. And can be explained in one image below. There are only a few things that might be novel to you, when coming from MS Word.

Vault | Folder. A folder that contains your notes with subfolders and files on one topic.

Note | File. A file in "markdown, .md" format, that you can open and edit with Obsidian, a text editor like Notepad or TextEdit. The title of the note will be the file name.

Link | Links between notes in obsidian are created by using brackets [[Name of Note to link]] and it not only allows you to click, but also to see which notes links where and who links back to it - a very powerful feature.

Tag | A tag or hashtag: #thisisatag . Obsidian will highlight it make it easy to find other notes with the same tag. Aside from a link, it is a way to group and connect notes in Obsidian.

MetaData | Some machine-readable data in a specific format. It helps with structure but is often irrelevant to the subject matter. For example "Year: 2019" or "DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-16381-2" are two pieces of metadata for a scientific paper. We can use this to create tables or lists automatically. (There are different ways of adding metadata)

Feeling overwhelmed? Think of it this way:

Obsidian is a fancy way to read, write and look at files(notes) in a folder(vault) on your computer. Nothing more.

There are a lot of tutorials on these very first steps of Obsidian out there. Check out the Obsidian documentation on how to create, titles, bold, italic text.

If you want me to make a specific one for academics, just shout out on Twitter or write me an email.

Now that you have an understanding of the basic building blocks like links, notes and tags, we can go ahead and create a system that you can use to organise 100s of papers. A system that will fit your thinking like a running shoe, making it comfortable to walk and talk.

SCTO System

My practice of writing notes has evolved over time, from the Zettelkasten structure. In science most of our knowledge at first comes from reading papers, of which we have to keep track meticulously as we condense and aggregate this knowledge. The SCTO system is designed to reflect this process and make it easy to condense insights from it.

Here is a breakdown of what the system encompasses, with details further down.

1. (Primary) Sources | In most cases, we create one note per paper I read. This note contains a summary, my thoughts and notes and includes the PDF file with highlights. Storing some metadata like DOI, tags, etc will enable it to be easily citable later on.

2. Compendiums | A compendium is a collection of findings, that either are directly extracted from the primary sources or are my own ideas. A finding is a short paragraph or sentence written in my own words. Each finding always has a link to its primary source. Once a Compendium has too many facts, I break it apart into multiple sub-compendiums.

3. Thoughts | Very often while reading a scientific paper we have an idea or question of the kind "What if I apply this technique to this problem?". More often than not someone did do it indeed, but it is of crucial importance for one's own thinking to keep writing down these questions. It nurtures your ability to be scientifically creative. No idea is too stupid, just write it down.

4. Ontologies | These are my own thoughts that are developed by reviewing Compendiums and comparing them with Thinking notes. A finished Ontology should aim at being a chapter of a review paper, or a proposal for a project.

Our information flows roughly in this order Sources → Compendiums → Thoughts → Ontology.

Why do it This Way?

Rather than building knowledge, you build understanding. You link pieces of information in a reflection of your own thinking process.

You will memorise the things you read better if you embed them into a context or network.

You always know your primary source and if needed can go back to it and look it up. Reviewing things in this way deepens your understanding. As we sometimes have to reread something from a different viewpoint to fully understand it.

You hone your own thinking and creativity by creating ideas and asking questions. This gives you an understanding of your own gaps in knowledge and highlights the possibilities where you can discover something novel.

If you do it right your Ontologies are almost directly "publishable", with a few separate tools you can even auto-generate citation lists and so on.

Obsidian becomes your one go-to tool for notes and citations - something that Mendeley or Zotero can only dream of.

Are you ready to make this small adjustment and supercharge your writing? Let's go.

(If you're impatient simply download the obsidian vault with this structure here and read through the notes therein.)

1. Primary Sources

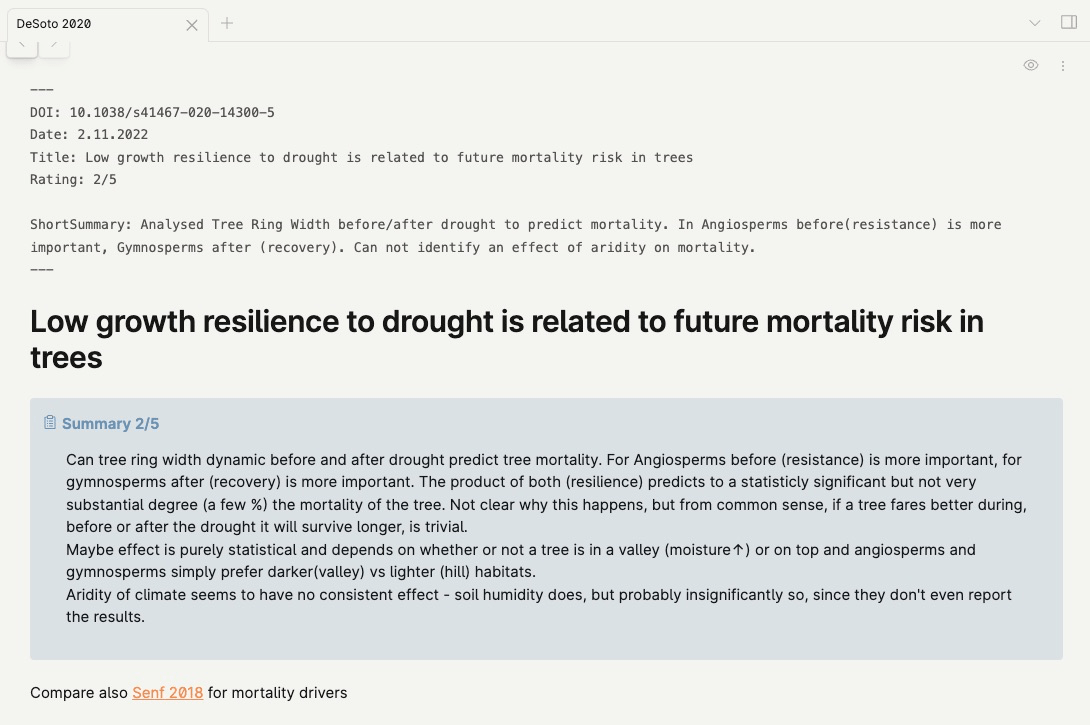

For each paper I find, I create a note from one template. This note contains a certain structure that works well for me, but might be different for you. It includes the following elements:

1. Metadata | DOI (for citing), Rating (how impactful I found this paper), Date (when I read it), One-sentence summary (to use in a table for example).

2. Tags | This becomes more relevant once you approach ~100 papers and need to organise them in some way. I work in computational ecology, so I switch between reading computer science, ecology, and mathematical literature. Typical tags for me are "#reviewpaper", "#machinelearning", "#ecology", "#foundation". Skip this part at the beginning if you like, as it is not overly essential.

3. Summary | Here I include everything that seems relevant about this paper in my own words. Also trying to highlight the uniqueness of the paper and the contributions of the authors. If I find something questionable I will note it here too. You can see an example below.

4. Quotable | Sometimes more practical than a summary. A quotable is a sentence that you could directly copy paste into a review paper. Writing it down this way, really forces you to think of the essence of the paper at hand. It also allows you to quickly write Ontologies.

5. Structure | A set of headers as a guide. Usually: "Aim of paper", "Data" and "Key Findings" for me. This is however not rigid. It should fit your domain. It is a simple reminder to aim to find the core of a primary source.

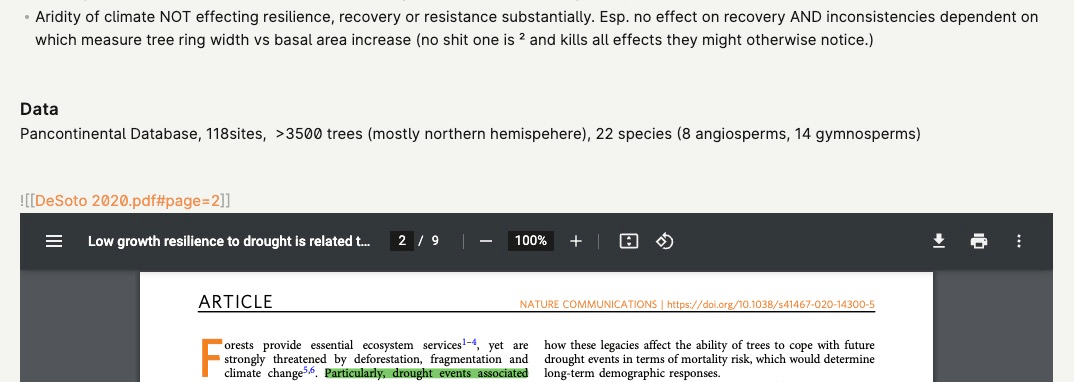

6. Embedded PDF file | Yes, you can store and embed PDFs in Obsidian. For a paper, I always embed the PDF at the bottom of the note. This makes it incredibly easy to access any figures, my own highlights, and so on directly from the source. Besides it makes it trivial to pass on PDFs to colleagues.

Once you have this setup you open your new note, fill out the metadata (in fact I have a script that does most of the tedium automatically), and start reading/writing.

By convention, I name the note and rename the PDF file to "FirstAuthor Year", as it is typical in a scientific citation.

You can embed a PDF by creating a link and adding an exclamation point in front of it. The screenshot below shows the embedded PDF that is titled like the note "DeSoto 2020.pdf". You can use your default PDF viewer and add highlights, since you are editing the PDF inside the vault, all your changes will be directly reflected.

Additionally and especially for books and very long PDFs, you can add #page=2 to link to the second page of the PDF for example.

Keep your PS notes short. Most of the information that you extract should end in a condensed form in a Compendium. This way you build silos of knowledge on a certain topic. The aim of your PS note is to create a quick reminder for yourself what this paper was about and is a primary source for. Particularly review paper notes tend to be almost empty.

Primary Sources are pointers and reminders, the bulk of your knowledge should reside in a compendium.

2. Compendium Notes

Think of a Compendium as a house where your facts live. You start with a few houses and keep adding facts to it as you go - over time it becomes a bustling metropolis with many houses. When I started learning Forest Ecology I had a single note called "Forests", that slowly grew (no pun intended).

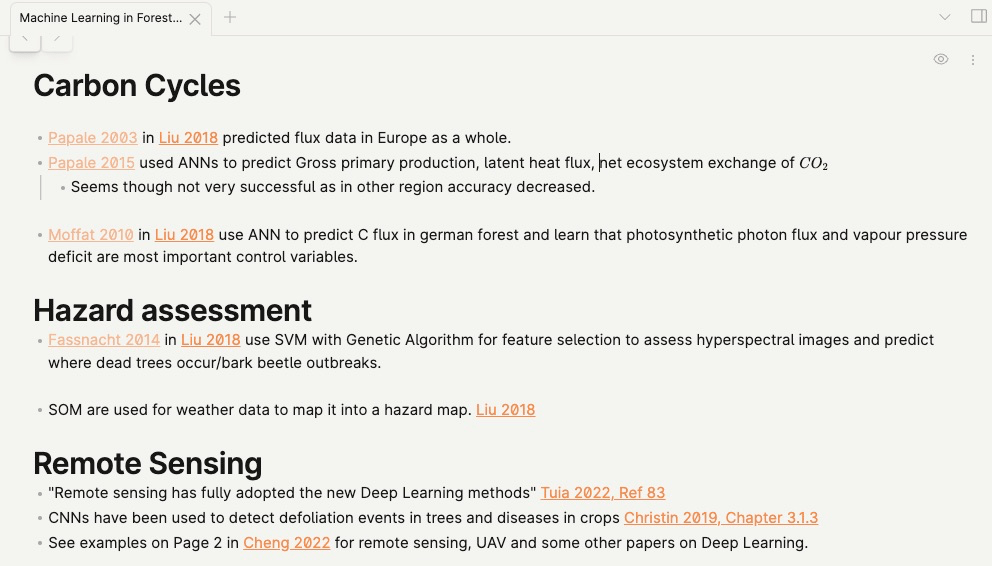

As you can see it is simply a collection of small statements in my own words. This helps me to learn what I am reading about and allows me to quickly review everything I know about a certain topic.

You will be surprised how useful such compendiums become over time.

At some point, you end up with compendiums the size of skyscrapers. Now is the time to start splitting things up. First by introducing titles and eventually by splitting everything under a title into a separate compendium.

Here is an example of the first separation of "Machine Learning examples in forest ecology".

Eventually, this note will grow into a set of notes like "Remote Sensing in Forest Ecology", "Hazard Assessment in Forest Ecology" and so on.

Bitesize Concepts

Very often when reading we come across concepts and ideas that are reflected in multiple places. A concept is something like "Biodiversity" for example. Ecologists have a myriad of ways to define and measure biodiversity. It makes, therefore, sense to create a concept compendium note dedicated to "Biodiversity Measurement".

It is in essence just a compendium note. My personal distinction is that I want concept notes to be directly linkable in text, while pure compendium notes are mostly for storage. So, if you will, a concept note is a bite-size compendium ready to be dropped into the flow of conversation.

Keep Track of your Primary Source

Remember that whatever goes into a compendium must have a primary source attached to it. As you can see in the examples above everything has a link to a paper.

More often than not your primary sources cite their own respective primary sources, that are probably not in your library yet. Review papers are not primary sources and yet initially you will generate most of your factual knowledge from those.

In that case, I use an alias link. An Alias link is simply a link where you change the text and it is done using a | or pipe symbol.

As you can see in this example I link the Review paper "Liu 2018", but the link text (anchor) is "Ref 99 in Liu 2018". So if at a later point, I use that piece of information, I will be able to quickly find the right reference by looking up in the bibliography of Liu 2018.

It is even better in papers that do not use numbers for reference but names. I could then write:

"Thessen 2016 in Liu 2018" is my anchor text.

For papers that you know you will be reading anyways, you can even create a link to a non-existent note. In this example "Papale 2003" is a paper I will read eventually, but have not created a note for. You can still link it and Obsidian will show it in a pale color. Simply clicking on it, will create the note for you.

Once the note with the title “Papale 2003” has been created all links are already automatically pointing to it and you do not need to update anything. Spiffy, ain’t it?

3. Thinking Notes

This is where you start turning someone else's knowledge in the form of compendiums into your own thinking, by questioning it, adding to it, and so on.

This section is entirely domain-specific, but it has the same rules as all the other sections:

1. Meticulously keep track of your sources and note down why and what you're questioning. For ideas note down for example that your idea is a combination of A, B and C.

2. Keep your notes short and well categorised, this will make reviewing them later a breeze.

Do not see Thinking Notes as a to-do list for yourself. (as in I need to answer all these questions), but more as memories of a thinking process that you are following.

Here is an example of an early Thinking note on creating an "Algorithm for Wetland Restoration".

It is important to revisit thinking notes often, this way you do not forget important aspects of your work. Often, especially when your questions are dated and you note that they already have been answered. Or that one of your ideas has already been done and there is an insight.

In that case do not simply delete your notes and questions, but move them to an archive. I tend to simply drop them into a subfolder "answered" and make a small note as to the result. You can review those much later, when you even forgot you had the idea.

Elaborate answers to your questions however are the crown of your knowledge process and deserve an ontology.

4. Ontology Notes

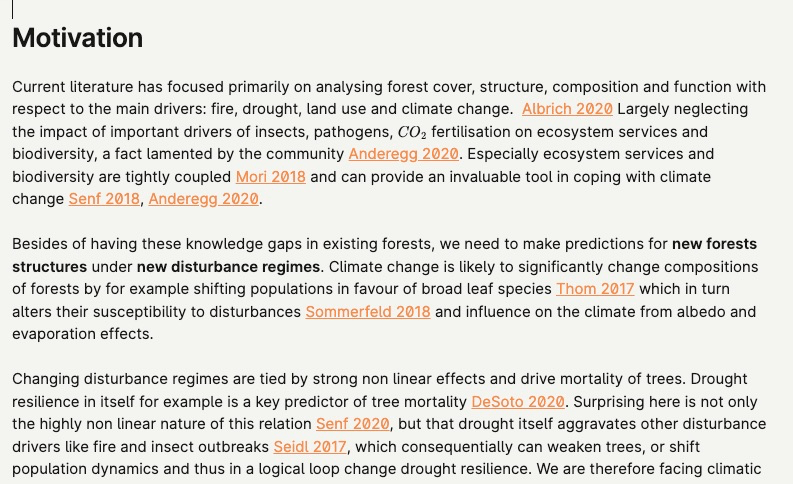

An ontology is defined as "a set of concepts and categories in a subject area or domain that shows their properties and the relations between them.". And it is exactly what it is. These are full-blown documents that explore a concept and come to a conclusion.

I tend to treat Ontologies as chapters or sub-chapters of a paper.

Keep in mind that it takes time to write ontologies. Don't rush it. If you have done your homework of organising the previous steps nicely you will now see the full advantage of this system in action. This is my strategy:

1. Look at your Thinking Notes and pick a topic or a question.

2. Comb through your Compendiums and gather all the facts related to this question into a list. It can be a temporary note.

3. Start writing using the facts (from Compendium Notes) to answer the question or summarise a topic (from Thinking Notes). Essentially you are adding these small bits together into a readable text. All there is to it.

Here is an example of an initial "Motivation" for my current project in forest ecology.

As you can see it already reads pretty much publishable. Yet all it is, is a collection of previously aggregated facts in compendiums. Take for example the statement in the first paragraph.

"Especially ecosystem services and biodiversity are tightly coupled [[Mori 2018]] "

It comes directly from a compendium note I aggregated to write the motivational introduction:

"Beta-Diversity Describes variation in species composition between adjacent locations [...] it will increase functions of ecosystems [[Mori 2018]]""

So all I did was to take a bunch of small building blocks, i.e. compendium entries like the one above, and assemble them into a readable text, using the primary sources I previously identified.

It takes less time to write whole pages of ontology notes once you have set everything up this way. Wonderful isn't it?

Summary

The system I present here has been honed over countless hours of experimenting, reading, writing, and reiterating on different topics. It is however only a starting point for your own system.

I am an ecologist, but an anthropologist or a mathematician could improve on it in the way they see fit. It is however a solid and battle-tested starting point.

Here is the TL;DR breakdown:

1. You gather your primary sources and create a note per source. Try to keep it concise and always tend to your meta data, it will be of much importance once your collection grows.

2. When you find a small "atomic" bit of information put it into a compendium note and keep aggregating those until they get too large. At this point split them into multiple notes.

3. Note down questions and ideas in thoughts notes that you have around the whole topic. Make references and comparisons to your primary sources. Do not try to answer them right away, just note.

4. Once reading your primary sources slows down to give you new insight, move on to reviewing your thinking notes, and pruning what questions are already answered or ideas invalidated.

5. Start writing ontologies, summaries, and answers to your own questions as you go.

6. Aim at making ontologies publishable and readable - something you can send to your colleague who doesn't know about your topic yet. These ontologies will be the basis of your next publication.

Download an example vault here.

I want to try this system !

I am glad you made it this far! If you like the idea. I created a small vault that you can download and start experimenting with. Simply download it here and open the folder with Obsidian.

If you like the content subscribe to the newsletter, follow me on Twitter. And if you really like it, then please share the link to this article on your social media.

And hey there is so much more to it. I have created a system of hot keys, and programmed different scripts that make importing and exporting easier. I also use a bunch of other tools that play well with Obsidian and can eliminate a lot of the tedium of organisation. Stay tuned.

Hi Jeannie,

yes but it requires a tiny bit of legwork.

1. You need one note per paper + its DOIs added at the top. (Doesn't work if your papers don't have DOIs, very rare these days though)

2. You need a plugins, either dataview or "datafolders"

Check out this thread how to create your citation list:

https://twitter.com/Artifexx/status/1603976132306796544

...but then found an evenbetter solution for "dataview" since it is not very user friendly. "Database Folders"

https://twitter.com/Artifexx/status/1604949090399555584

Hope that helps!

Hi Ernesto,

You're right having one source note per book might be a bit of an overkill - unless for example it is a novel that you just need minimal notes on.

Here you have to try find a solution that works - My idea would be to break it up into chapters and have a source note per chapter. Especially technical books often have unrelated chapters.

The DOI i keep to be abtle to use bibtex & create citations. But it is by far not the only system in use.

I would find out how the book you are reading is usually cited - there will be some number there. Store this number so you have a citation key for this book later on. I have not tried it personally though.