Workshop: AI-powered Literature Review

Let's combine AI, conceptual notes and a "detective" approach into the most effortless literature review workflow yet. Here's how it works. Demo in webinar on July 29th.

My blog has moved

If you want to receive regular updates, new content and updates check out the website.

Not too long ago someone reached out to me and said that they have collected 100s of papers on a topic and are now just stuck in their literature review asking for help. I call it a collector or breadth-first mindset: Gather all the ingredients then start working. We do this because it feels rewarding to accumulate.

But, in the long run, the collector mindset leads to exhaustion. Just thoroughly reading 3-4 papers and writing some notes can take a whole day. Doing that for 100 papers is more work than you can do in a month. Of course it’s terrifying!

A better way is the detective or depth-first mindset. This involves just starting with one to two papers, looking for questions or “rabbit holes” that are worth pursuing next, usually in the form of a reference. Then, just like a detective, you pick the next clue and read the paper that contributes the most to solving the mystery of your subject.

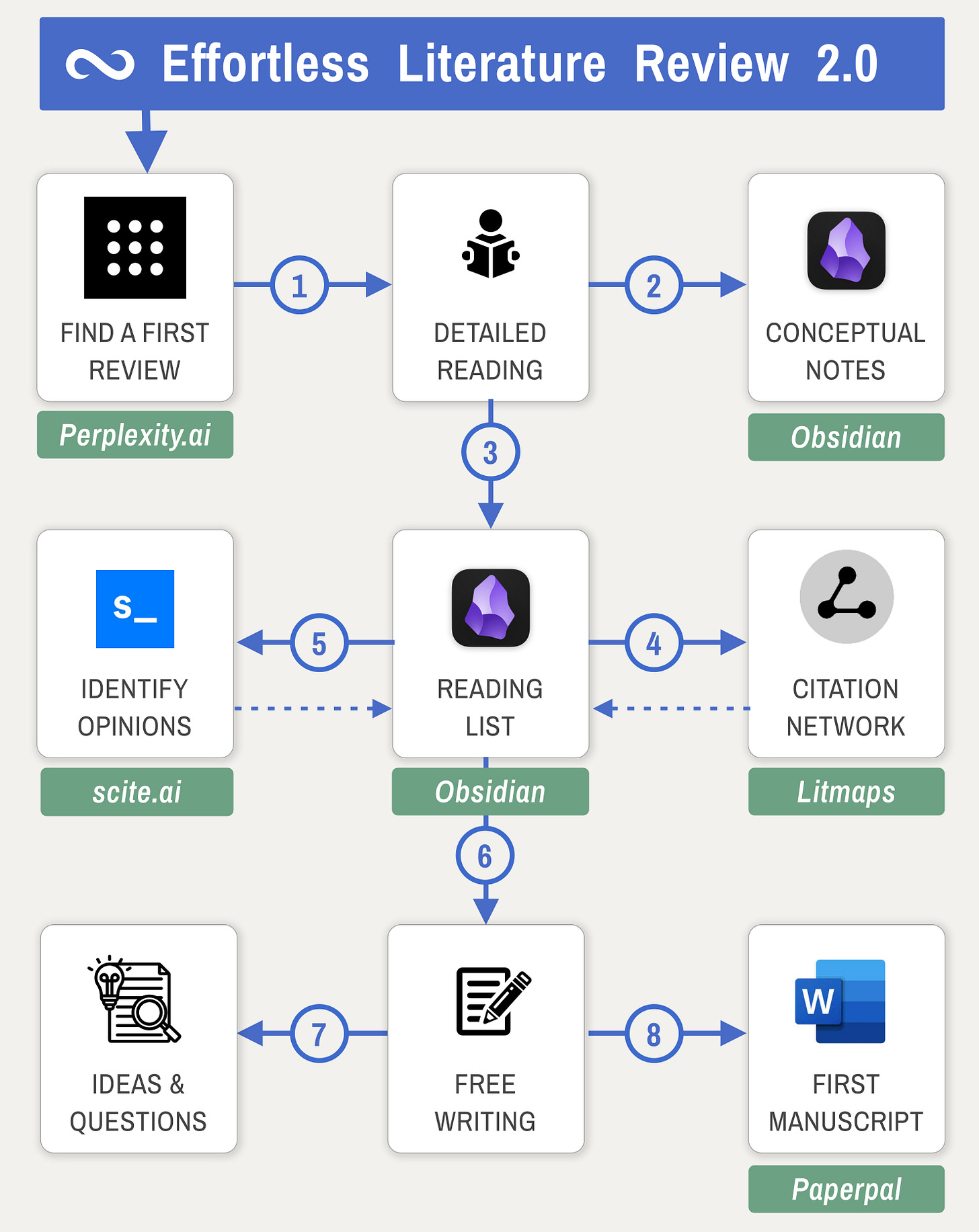

This is the workflow I am using:

Below you will find an overview of the different steps. But workflows are best shown not read, that is why I decided to make a webinar. Join it today:

Step 1: Getting started

Up until just a few months ago I used Google Scholar to look for papers. But with the rise of AI, I found a much better tool: Perplexity.

Think of Perplexity as a ChatGPT and Google combined. Ask a question in plain English and it will reply likewise, plus give a set of links to papers (or articles). The answer feels a little bit like an academic paper itself.

Remember, we want to be a detective, so we are looking for a paper that has the most clues. Academically speaking, these are usually review papers. In the example above I found a paper called “Trait-based modelling in ecology: A review of two decades of research”. That’s exactly what I needed.

You can find more info on Perplexity in this thread.

Step 2: Detailed Reading and Note Taking

Instead of looking for more papers, let’s indulge in the review we found. We want to solve the research mystery at hand; in my case, how scientists model functional traits of plants! The paper should have some answers.

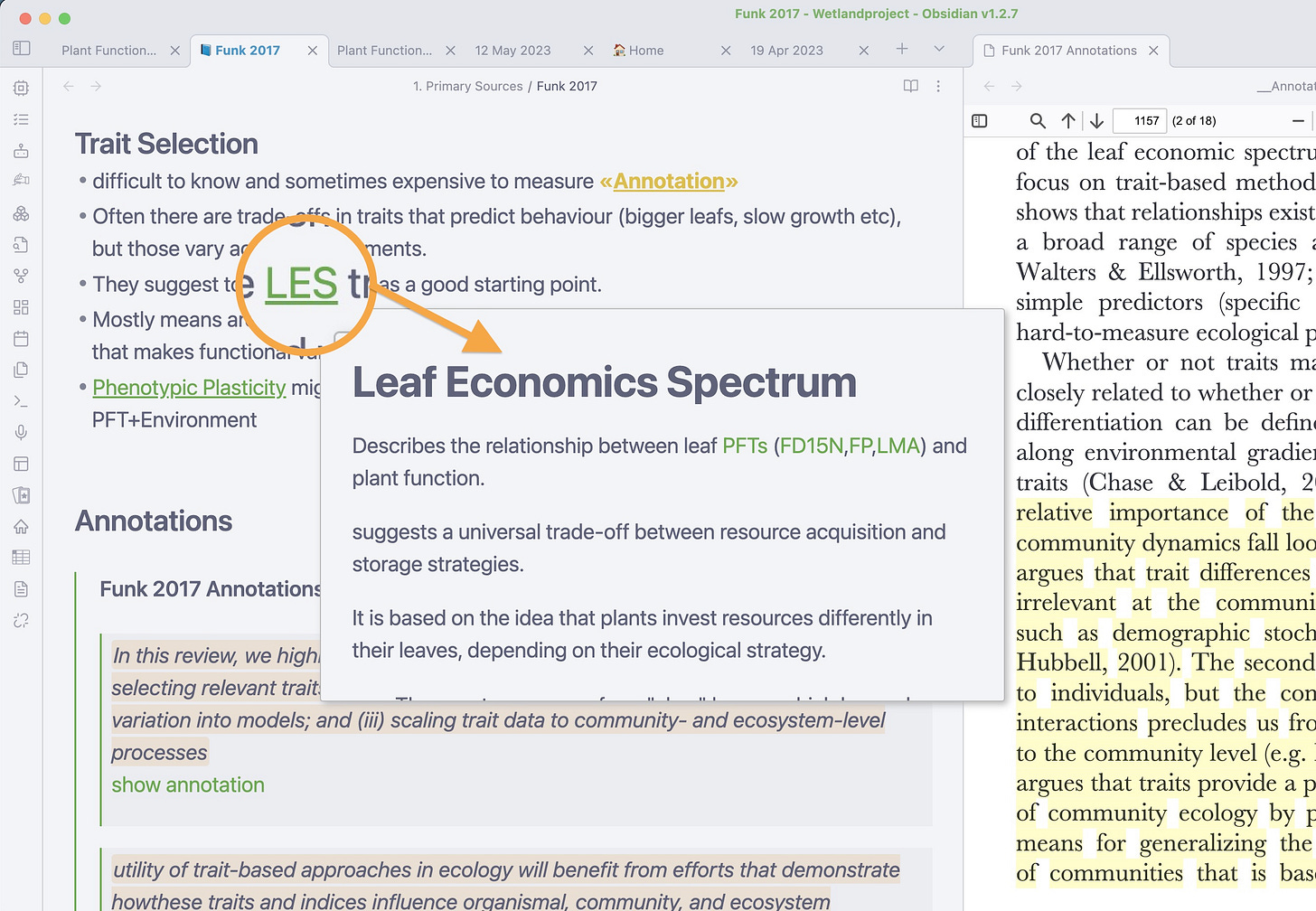

Read the paper with full attention, even if takes you several hours. Every time you identify a concept, take a note. Over time you will build a “personal Wikipedia” of your research. I recommend using Obsidian for this part, as I’ve found it’s by far the best note taking tool for academics.

Break up the findings into concepts and ideas. Create notes for each.

Link those notes heavily to one another; this will help to discover ideas later

Keep track of your sources. If you learn about a concept in a paper, link the paper.

You can read more on how I take notes here. If you really want to really excel at note-taking get a copy of the Effortless Academic’s Manual, my 9-hour online course, that covers all the theory and practical advice you’ll need.

(Participants of the webinar, will get a 30% discount for this course.)

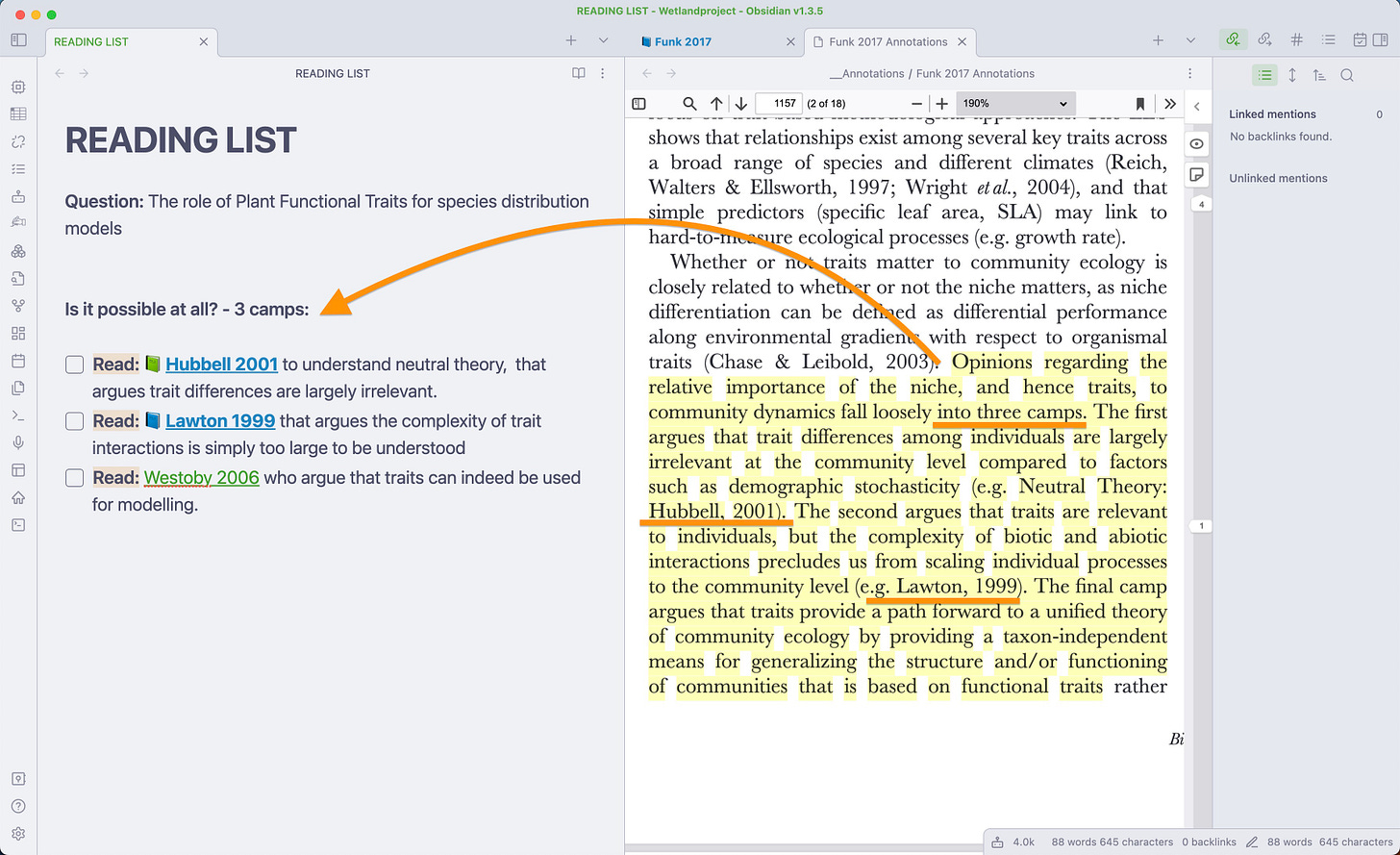

Step 3: Creating a list of clues

Good review papers will present contrasting points of view and cite their respective references. These are the passages that contain the clues for your next read.

In my case, there are three camps in the literature: one argues that modelling functional traits in plants is impossible, one says it’s irrelevant (because things are mostly random anyway), and the last keeps trying. These are the three clues!

I write them down in a reading list. The most important part is that you don’t just dump a reference. Instead, describe exactly why it’s important to read this paper. This will be invaluable, especially as your list grows.

You can even expand your reading list into a “Dashboard” to stay organised. This thread has more information on the whole process. And this thread describes how to build a project page for your literature review.

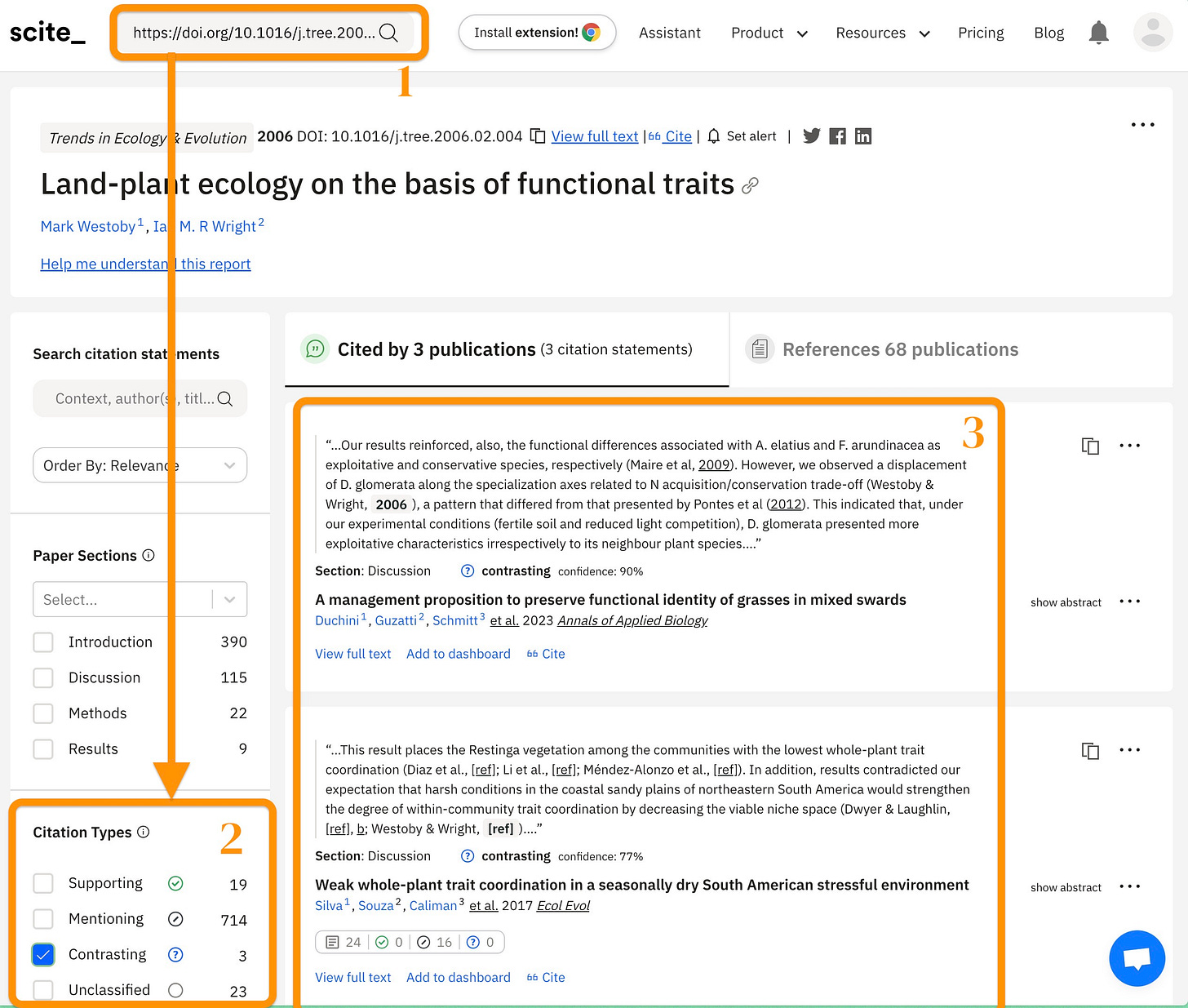

Step 4: Using Scite and Litmaps

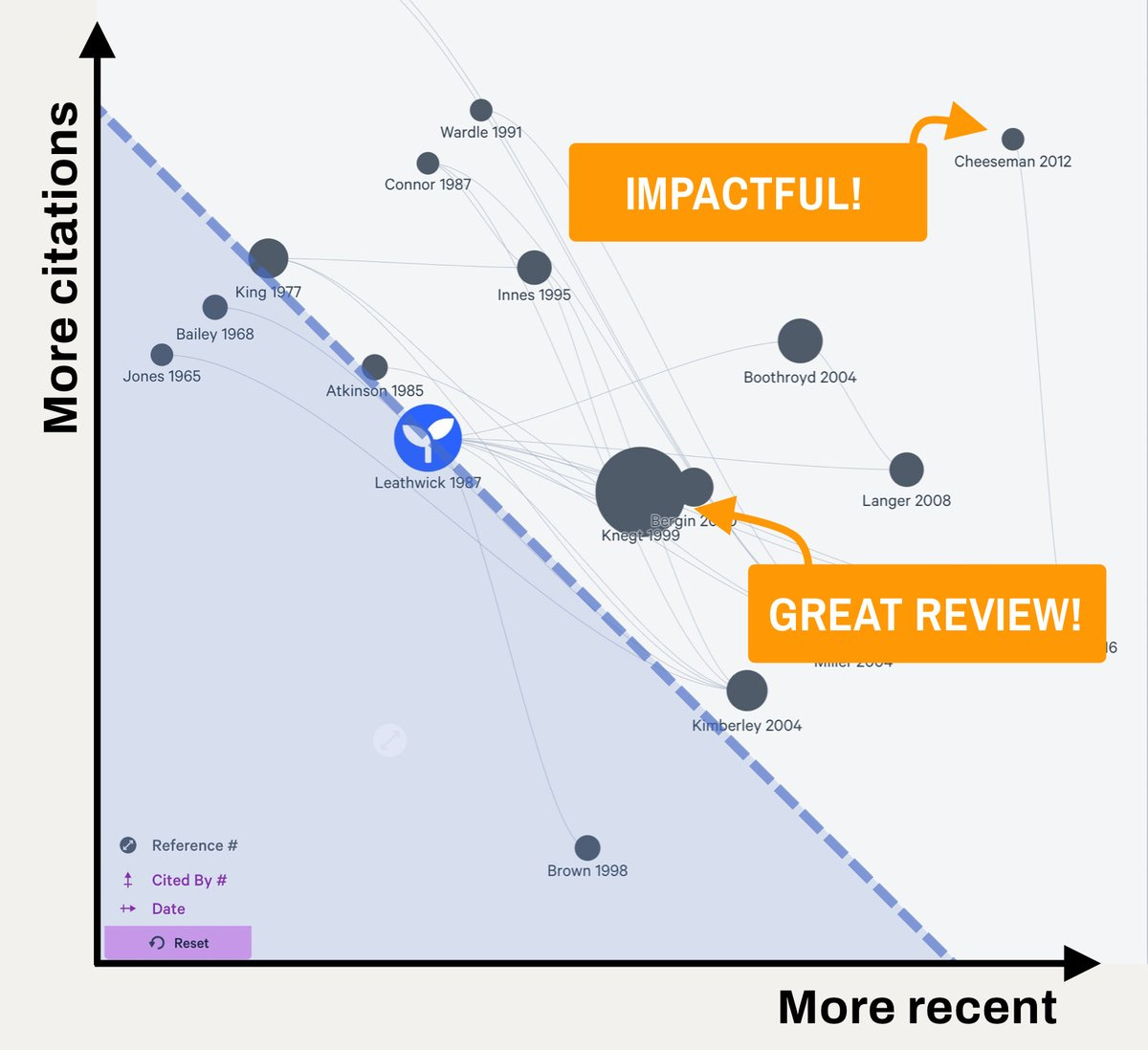

These two tools allow you to dig deeper (Scite) or broaden your scope (Litmaps). The method we used in Step 3 can only find studies published before the publication date of the current paper we are reading. But, if our review is already five years old, then we need to find relevant literature after the publication date.

This is what Litmaps is for. One of its most useful features is called a “Seed Map”, which takes a single paper and gives papers before and after its publication date, sorted by the number of citations they’ve received. Most importantly, it’s arranged in a graphical fashion, where I can instantly see what is impactful.

If you have been following me, you know that I am a huge fan of Litmaps. Read more about how it works in my original post on literature reviews or in this thread.

Scite, on the other hand, is a tool to dig deeper. If we give it a paper, it will give us all the studies in the future and tell us whether those studies supported, contrasted or just mentioned their findings. For review papers, most papers will be "mentions”, but for original or provocative ides you will find the relevant papers that are for or against the presented point of view.

Scite also released an AI assistant not too long ago, you can read about it in this thread.

Step 5: Bringing it all together through writing

One of the most useful techniques to build a coherent argument is to start writing what you realise. More often than not you will identify questions you were not aware of, and a quick search adds another paper to your reading list.

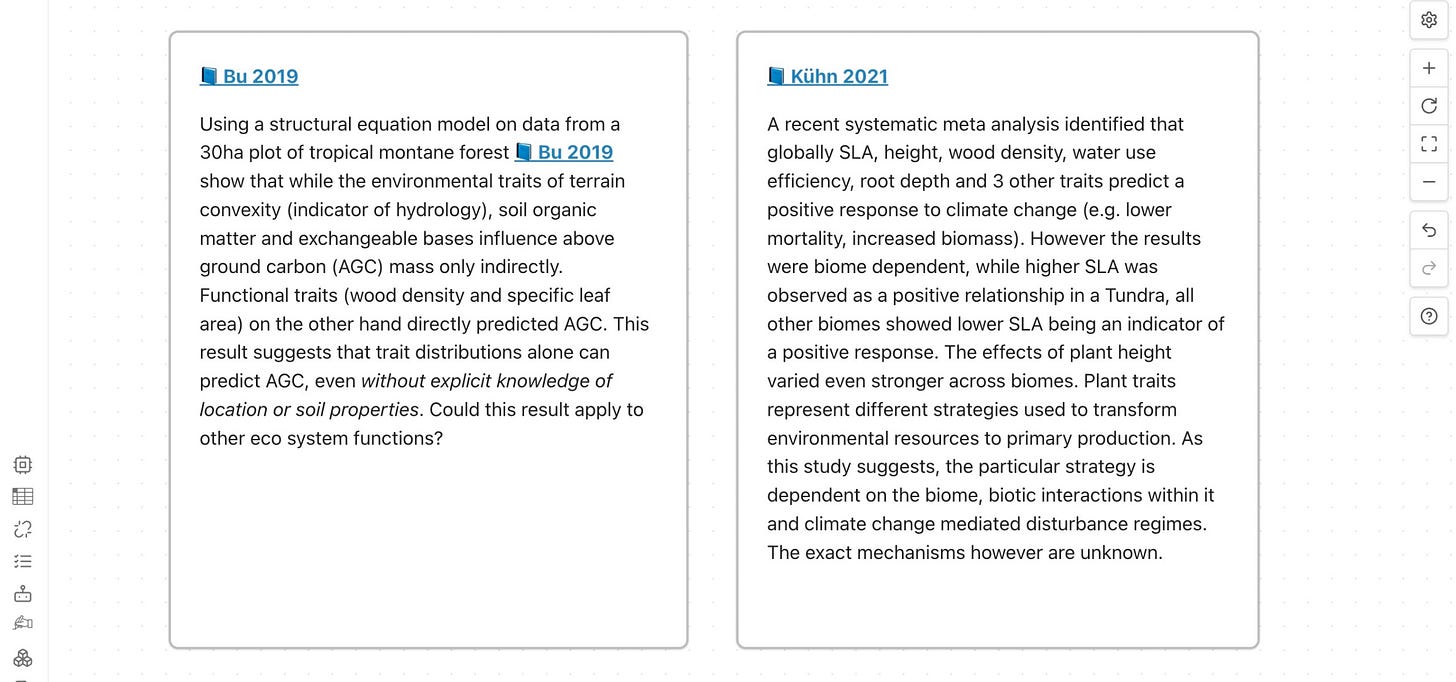

Start small by reviewing a few papers you’ve read with just a paragraph each. Here’s how it can look:

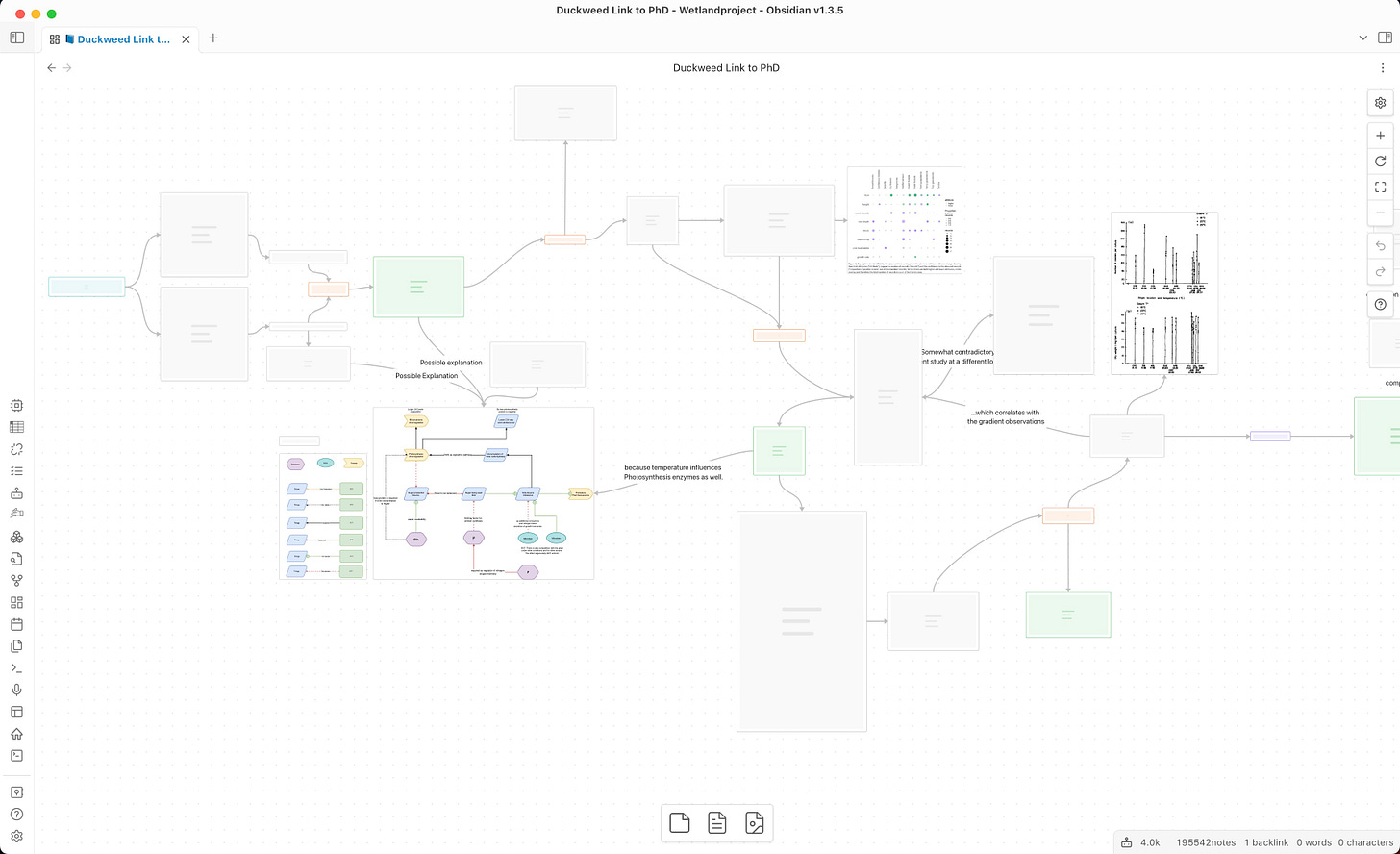

My favorite tool to take notes or write is Obsidian, partly because it has a very useful feature called Canvas. Canvas allows you to lay out notes, images or text and connect them with arrows — perfect for building arguments. This thread has more info.

Over time, you can build an entire argument as a map. Here is an example.

In the zoomed-in version below, you can easily see the links to papers are directly integrated. Additionally, colors are used in a meaningful way, i.e. orange for questions, green for explanations and white for text.

My Blog has moved

If you want to receive regular updates, new content and updates check out the website

Step 6: First draft

The last step is something no tool can do for you: writing. The very first draft can be written in Obsidian, but later I tend to move to Word, especially when collaborating. Paperpal is one of the tools I recommend to correct issues in your writing. It’s use is straightforward: install the plugin for MS Word and accept/reject the recommendations it makes. You can find details in this thread.

If you are using Overleaf for your papers you can also use the web version of Paperpal to work through your draft.

Summary

This is what I call the detective approach to literature reviews: instead of collecting papers on a topic, we start with a single one and gather clues on the question we try to answer. Perplexity.ai is a great AI search engine for this first step. Litmaps and Scite help you gain more breadth (similar and future papers) and more depth (contrasting or supporting literature). Writing your findings using Obsidian Canvas is extremely valuable, as it condenses your knowledge and creates questions. Lastly, we can use Paperpal to brush up our writing to a final first draft.

If this process still sounds abstract, then consider joining my upcoming webinar. I’ve gathered dozens of examples for these steps that we’ll go through in detail.

Join us on July 29th (or as a recording later). You will have the chance to submit your personal questions before the webinar to make it relevant to you.